When Bayesian Uncertainty Becomes Memory - A Path to Continual Learning

“Knowing what you don’t know” is a phrase that’s often misunderstood in Bayesian deep learning. The naive interpretation is that a model simply becomes uncertain when it encounters data different from its training set. In reality, a Bayesian model’s “knowledge” is initially governed by its prior — an abstract construct that’s usually far from human-interpretable. So while the model may know what it doesn’t know, we humans often don’t know what it knows.

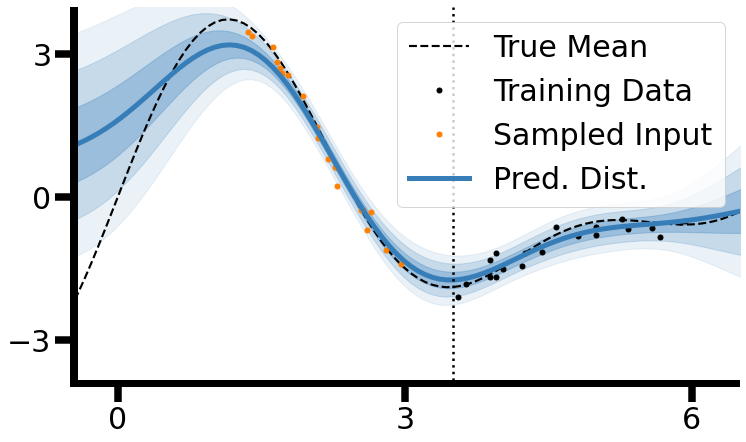

Towards the end of my PhD, I was working with my friend and co-author Francesco D’Angelo on a paper exploring this very issue (D’Angelo* & Henning*, 2021). In this blog post, I discuss how the notion of “knowing what you don’t know” becomes meaningful for continual learning once uncertainty is directly tied to the observed training data. In our paper, we illustrate examples where epistemic uncertainty begins to mirror the underlying data distribution.

This connection gives uncertainty a generative flavor. And when uncertainty becomes generative, something profound happens — continual learning is solvable as a side product. If uncertainty reflects the density of what has been learned, then sampling from regions of low uncertainty is equivalent to replaying what the model already knows. That’s the essence of what we called uncertainty-based replay.

A Short Detour: Bayesian Learning and Continual Learning

For a proper introduction to Bayesian statistics and continual learning, see Chapters 3 and 4 of my thesis: (Henning, 2022).

Continual learning is usually described as the challenge of learning a sequence of tasks — say, recognizing trees, then flowers, then animals — without forgetting what came before. Most machine-learning models struggle because learning a new task often overwrites parameters acquired from previous tasks, causing catastrophic forgetting.

In principle, Bayesian statistics already offers a mathematically elegant solution. The recursive Bayesian update tells us exactly how to incorporate new data:

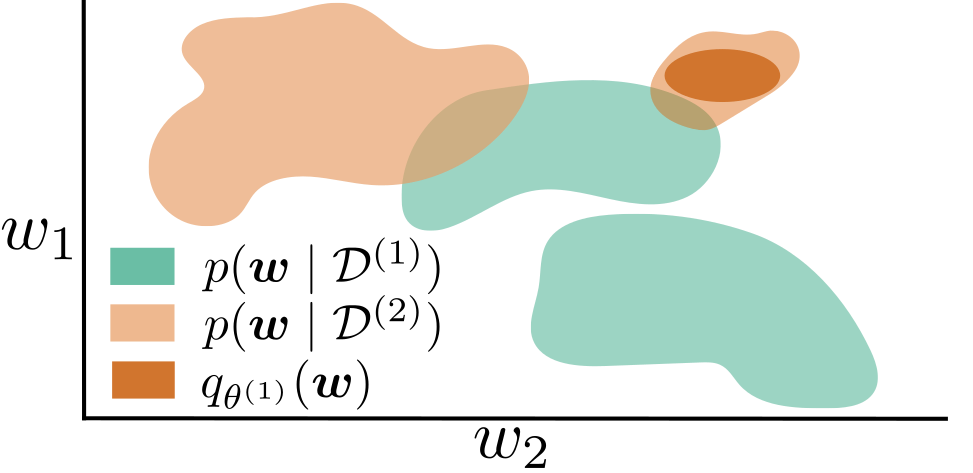

\[p(\mathbf{w} \mid D_{1:t}) \propto p(D_t \mid \mathbf{w}) p(\mathbf{w} \mid D_{1:t-1})\]This formula says: use your previous posterior as the new prior — the old knowledge naturally carries forward.

If we could compute this update exactly, continual learning would be solved. The model would integrate new information while preserving everything it had already learned. But in practice, these updates are intractable for complex models, and approximations like variational inference or Monte Carlo sampling often fail to capture true posteriors.

In this post, we explore a different perspective: instead of trying to solve the Bayesian update, we use Bayesian uncertainty itself as a tool for continual learning.

It’s a method that only works if the prior is chosen just right — but when that’s the case, uncertainty itself becomes memory.

When Uncertainty Becomes Generative

What a Bayesian model “doesn’t know” depends entirely on the prior (the assumptions it carries before seeing any data). A good prior encodes an inductive bias: it guides generalization, shapes how the model extrapolates from few examples, and defines what kind of uncertainty is meaningful.

In Bayesian neural networks, however, priors are typically defined in weight space, often as zero-mean Gaussian distributions. This is mathematically convenient but conceptually arbitrary. Its effect in function space, where the model actually operates, is unpredictable and usually meaningless.

As a result, the model’s uncertainty tells us little about the structure of the data it has seen — it’s just variance around arbitrary parameter settings.

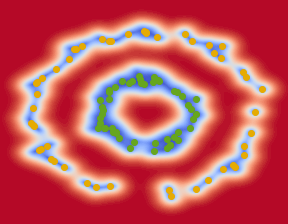

But there’s another way to think about priors. Suppose we choose a prior that reflects the data distribution — one that, once updated with real examples, concentrates uncertainty along the data manifold. Then the posterior uncertainty ceases to be an abstract measure of ignorance. It becomes a map of experience.

In this view, uncertainty isn’t merely epistemic; it’s generative. Sampling from it can recreate plausible variations of what the model has already seen.

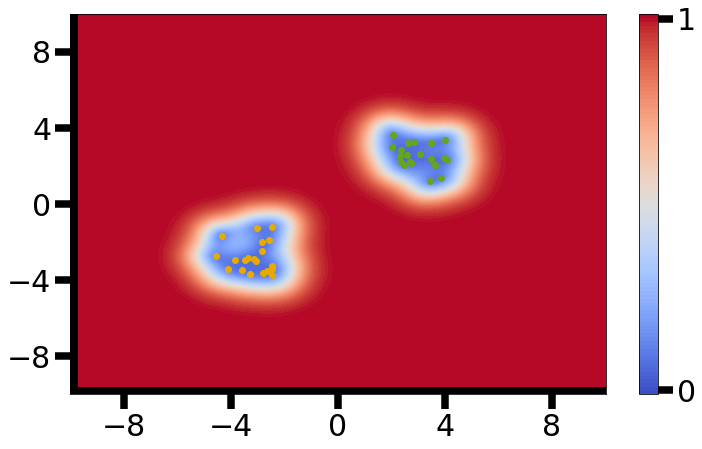

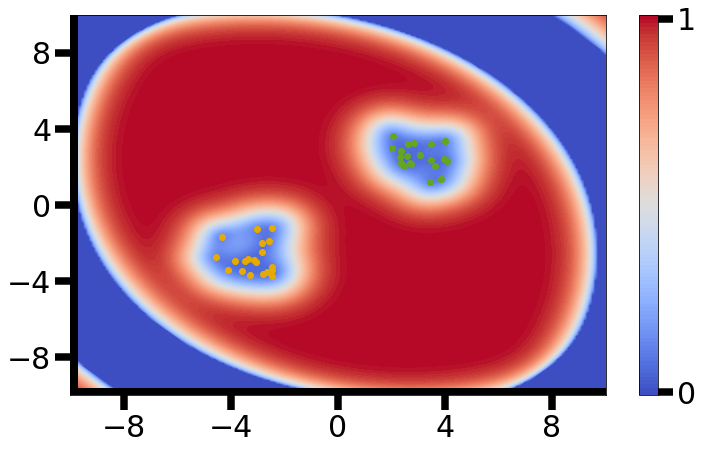

Francesco recognized a beautiful connection here: in a Gaussian process with an RBF kernel, epistemic uncertainty is mathematically related to the inverse of a kernel density estimate with a Gaussian kernel (cf. Section C in the supplementary material).

In other words, the regions where the model feels most certain are precisely those where data density is highest — and that’s the bridge between uncertainty and memory.

Uncertainty-Based Replay

Once uncertainty becomes generative, continual learning stops being a separate problem.

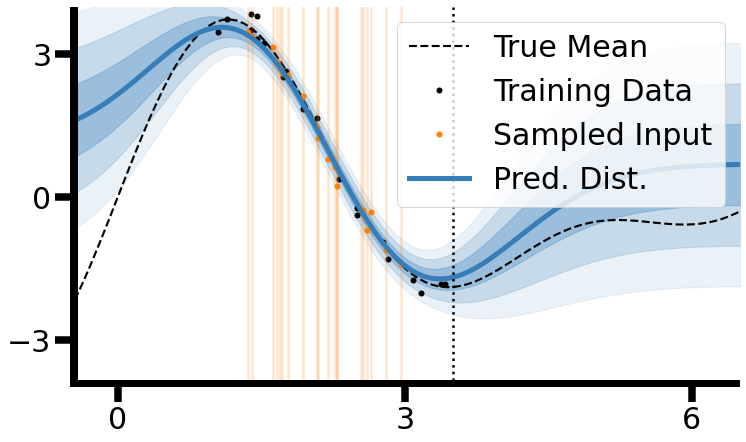

A model that can sample its own past from uncertainty no longer needs external memory. Its uncertainty is the memory — a compact, probabilistic summary of past experience encoded in the posterior.

Whenever a new task arrives, we can sample synthetic examples from regions of low epistemic uncertainty — regions corresponding to what the model already “knows”. By mixing these synthetic samples with new observations, we effectively reconstruct an IID-like dataset approximating all observed experience (past + present). Training on this joint dataset prevents forgetting, just as if we had stored all past data explicitly.

This is the core idea behind uncertainty-based replay. In classical generative replay, continual learning requires two models: one for the task, another (often a VAE or GAN) to imitate past data.

Here, the Bayesian model simultaneously serves as learner and generator, exploiting its own uncertainty structure to replay experience.

In practice, this idea only works if epistemic uncertainty correlates with data density — as in the RBF-kernel case above. When that alignment holds, the posterior variance effectively is a generative model of past observations. When it doesn’t, uncertainty degenerates into noise and replay collapses.

Still, the conceptual simplicity is striking: by inverting uncertainty into density, a model can recreate its own past and learn continuously — no extra parameters, no external memory, just a well-chosen prior.

Closing Thoughts

This is a conceptual demonstration — a small excursion into how Bayesian models could, in principle, learn continually.

In theory, it’s beautifully simple: uncertainty doubles as memory. In practice, it’s brutally difficult. Choosing a prior that induces the right inductive bias — and approximating a posterior rich enough to preserve it — remains an open challenge.

Yet the idea is compelling. If the brain operates (at least approximately) as a Bayesian system, then uncertainty-based replay might not be far from what biology already does.

Sleep could act as nature’s generative replay phase, resampling from internal uncertainties to consolidate and refine past experiences.

Continual learning, then, is not just about retaining the past — it’s about imagining the past in ways that preserve learning and enable future adaptation.

References

-

On out-of-distribution detection with Bayesian neural networksSee also our shorter workshop paper , 2021

On out-of-distribution detection with Bayesian neural networksSee also our shorter workshop paper , 2021

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: